Milli Vanilli, guitars, and the fight for humanity

Musicians faking it is a tale as old as Top of the Pops. But with AI generated music the crisis of authenticity is striking at the core of what it means to be human

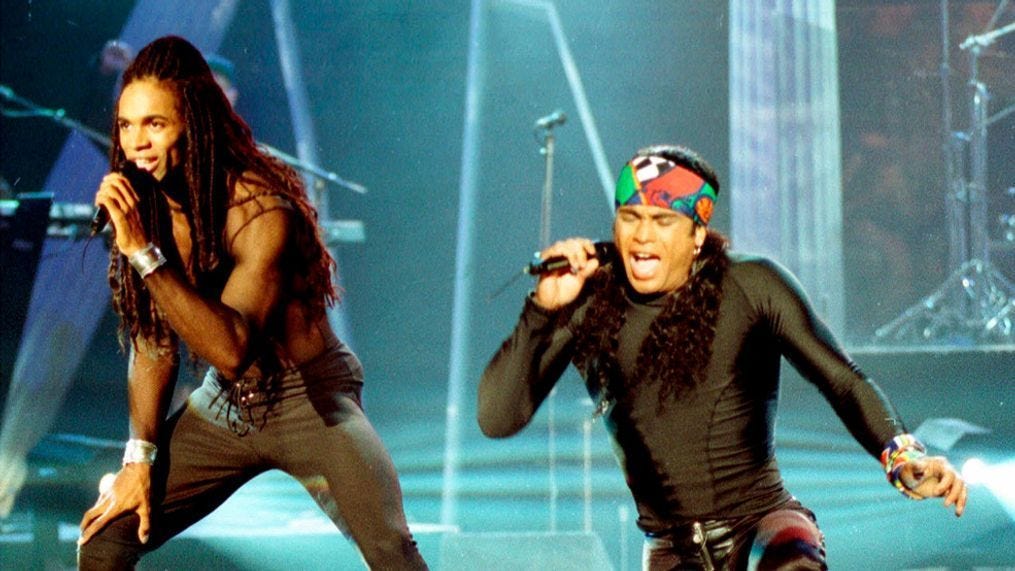

ONE OF THE ODDEST MUSICAL SCANDALS of the late 1980s was the case of Milli Vanilli, an R&B duet from Munich that sold over 30 million records internationally with hits such as “Blame it on the Rain” and “Girl You Know It’s True.”

They won a Grammy award in February 1990 for Best New Artist, but it all came crashing down that November when their producer, Frank Farian, admitted that neither member of the group – the Frenchman Fab Morvan and the German Rob Pilatus – had actually done any singing on their records, and their live performances were all lip-sync’d to backing tracks. Their Grammy was promptly revoked, and there was even a class action lawsuit on behalf of record buyers who had been “defrauded.”

In a sad coda to it all, they attempted a comeback of sorts in 1997, but it was cut short after Pilatus spent time in jail for assault and robbery, and then died in a drug overdose in early 1998.

What is weird about the whole affair is that no one could have seriously believed that Rob and Fab were anything more than the Zoolanderesque karaoke frontmen for an entirely manufactured act. To begin with, their producer, Frank Farian, was the brains behind Boney M, another famously cooked-up group of lip-sync’ers. Second of all, all you had to do was watch any interview of Rob and Fab speaking to know that there was little to no chance these two disco club rats were the voices of Milli Vanilli. And as early as summer 1989, there was an incident where the duo were singing live on MTV when the recording jammed and started skipping, at which point Pilatus ran off stage in a panic.

Indeed, as a 2023 documentary confirmed, pretty much anyone remotely associated with the industry knew what was going on. And even the audience didn’t seem to care much one way or another. What really catalysed it as a scandal was when one of the guys who actually did the singing on the record complained publicly about his lack of credit, and exposed Morvan and Pilatus as “imposters”. At this point, everyone had to pretend to be shocked and/or apologetic, while Rob and Fab were hung out to dry.

This past spring, a scandal with a similar narrative arc played out in a much more niche community, that of electric guitar YouTubers. Like virtually every other hobby community or cottage industry on Earth, there is a large online community of guitar players offering a mix of tips and tricks, serious instruction, gear reviews, and show-offy technical set pieces.

One of the more popular of these influencers is (or, was) a 20-something Italian funk musician named Giacomo Turra, who has three quarters of a million Instagram followers, a substantial following on other platforms, and a signature guitar with D’Angelico. I followed Turra, and though I wasn’t really a fan of his music his videos were entertaining and highly produced jams with other musicians. But one thing was pretty obvious: he wasn’t playing live on his videos – he was clearly miming the guitar parts to pre-recorded tracks.

Lots of YouTubers do this. And even though there is a subplot in the guitar YouTube world where people step through videos frame by frame trying to “out” those who might be faking it, many people defend the practice on the grounds that as long as you actually wrote, and can actually play, what you are miming, then it’s not a big deal to air guitar it for the perfect internet take.

But a couple of months ago, a British bass player and YouTuber with half a million subscribers named Danny Sapko put out a video taking down Turra for a number of other more serious crimes. As Sapko discovered, not only was Turra miming his guitar playing, in some cases he was actually fake playing the piece at a slower tempo and then speeding up the video, to make himself look like a better player than he was. Worse, there was strong evidence that the songs he was playing over weren’t even actual guitar parts, but computer-generated tracks from a notation software. Finally, another musician jumped into the comment boards under Sapko’s original video to point out that a lot of Turra’s most popular pieces were stolen from other musicians, and Turra wasn’t flagging them as cover versions, he was claiming them as his own. He was even stealing the entire arrangements and solos.

The whole thing blew up hugely. Almost every major guitar YouTuber put out a video giving their take on the scandal, though probably the most devastating came from Rick Beato, who is the closest thing the community has to a wise elder. As Beato told his five million subscribers, he had actually filmed a session with Giacamo Turra, but had quickly realised that “he wasn’t good enough to be on my channel.” Turra’s half-assed apology only made things worse; the outrage turned into a pile-on, complete with slightly cruel parodies.

As with Milli Vanilli, one of the problems with analysing the scandal here is figuring out precisely just what Turra did wrong. The musical theft and plagiarism is obviously serious, and lots of people pointed out, with considerable indignation, that Turra had helped himself to songs from musicians with far greater ability, but far fewer followers.

If musical theft is the crime, Turra is guilty as charged. But to a large extent, the plagiarism was understood as a relatively small part of a bigger problem, which is that Turra was faking all of it: the playing, the skills, the pretend live performances. What seems to have happened here is that, like Rob and Fab, the Turra scandal exposed something that the guitar community knew was widespread, but which everyone had agreed to pretend wasn’t happening, or at least not make a big deal out of. Once Sapko’s video hit, it became impossible to ignore, and Giacomo Turra became the lightning rod for a great deal of pent up anger and hostility in the online guitar community.

Yet behind all the contempt directed at Giacomo Turra there is something else at work: fear. The thing about electric guitar is that it is one of the last redoubts of the old analog culture. An electric guitar running through a tube amp cranked until it breaks up and distorts remains the craft’s defining aesthetic, and has been the organising principle of the vast majority of all popular music released since the early sixties. But that has been compromised in any number of ways over the years, from digital effects processors to GarageBand for recording to modelling amps to digital pickups that allow you to change the very essence of your guitar at the push of a button.

In his own take on the Giacomo Turra affair, a guitarist named Troy Grady put the situation in stark terms. He starts by conceding that musicians miming is nothing new; from Soul Train to American Bandstand to Top of the Pops, big acts have air-banded their way through the studio versions of their hits.

But what distinguishes those bands from YouTube fakers like Turra are the audience expectations. Everyone knew the acts on these shows were faking it – sometimes the bands even made fun of it on stage (like in this video of Michelle Philips eating a banana while “singing”, or Nirvana taking the piss on Top of the Pops). With Giacomo Turra, it was just layer after layer of deception by a guitarist with a fictional skill set, whose entire performance is a lie. It’s like if Rob and Fab weren’t even real people, and Milli Vanilli’s songs weren’t real songs, and the session singers weren’t even real singers, but instead it was all a digital concoction.

Two years ago, Rick Beato interviewed Billy Corgan for his channel. Their conversation is 90 minutes long, and it is a fabulously thoughtful and engaging discussion about the creative process, the mechanics of recording music in the nineties, and the birth of the grunge scene. But toward the end, Beato tries to draw Corgan into some criticisms about the present state of the music biz. He begins with a softball, asking Corgan what he thinks about the way TikTok drives the music business today.

But Corgan doesn’t bite. Instead, he says that “kids are going to gravitate to excitement. You can’t look askance at kids gravitating to excitement in a dopamine rich society. The artists just need to figure it out.”

Beato tries another tack: “But are you glad you [Smashing Pumpkins] came around in the pre internet, pre social media, pre cell phone era?”

Again, Corgan declines the easy dunk. Instead, he suggests that Smashing Pumpkins would be an even bigger band if they came out today: “We were a perfect band for social media,” he tells Beato. “We were visually rich, with strong personalities, we would have done well.“ Then he adds the kicker: “I don’t blame kids for leaning into the modern world.”

But then Corgan himself raises the ante, and suggests that the real problem for artists is looming with the rise of artificial intelligence: “We are on the verge of AI systems that will make learning to play an instrument redundant. I’ll bet you in 20 years there will be artists who will just program music” through AI systems. After Beato proposes that it is actually more like three years out, Corgan replies sure, whatever. The point is that AI systems will completely dominate music. An intuitive artist beating an AI system will be very difficult, since a musician will be able to play three notes outlining an idea and the AI will do the rest. They will get rich, and “no one will care if they can’t play, or don’t know a 7th or a 9th chord.”

Corgan ends up arguing that in the grand scheme of things this is just the way of the world, and there’s nothing inherently wrong with it. At the very least, there is no point in yelling at the tides. But he concedes that something will be lost along the way. Making music, Corgan says, is a deeply emotional intuitive process that takes time; more than anything it is an exploration of self. And, he concludes, “No AI system will ever trump that journey.”

Note that he’s not claiming that no AI will ever make music that could sound as authentic and resonant as, say, Nevermind or Siamese Dream. It’s a more profound claim: that making music is part of the human process of self-discovery, which is worthwhile and valuable for its own sake. And no machine can do it, precisely because they are not human.

Or as Troy Grady concludes his own video about Giacamo Turra:

This is more important than ever, people. We are fighting for our creative lives against the rise of the machines. Clarity about what you are presenting, whose work it really is, is the line between art and artifice.

At any rate, it turns out that Rick Beato was optimistic by about a year. This past week saw the appearance of a band called “Velvet Sundown”, an obviously AI-generated group whose computer generated songs included such titles as “Dust on the Wind” and “The Wind Still Knows Our Name.” After a week of speculation, a “spokesperson” for the band acknowledged that it was all AI, and called it an “art hoax”.

It is actually more like a probing operation in what is shaping up as a multi-front battle not just for creativity, but for humanity itself.

From the X-Files:

I recently came across “Why the nineties rocked: Back then we still had a future to yearn for” — a 2022 piece by Douglas Coupland from Unherd.

“The death of the summer job” (I want to write something about summer jobs soon).

“Gen X? More like Gen Sex” — Mireille Silcoff continues to build her brand

I’m dying to read Cold Glitter: The Untold Story of Canadian Glam by Robert Dayton. I read about it in Michael Barclay’s substack which is the closest thing to an alt-weekly you are going to find. Subscribe!

The alt title for this post was rAIge agAInst the mAchInes

Great piece! I missed that Nirvana "performance," somehow, but your reference has inspired some poetry:

Nirvana on Top of the Pops

forbidden from playing

their instruments

three free-spirited

kids from Seattle

burlesque the motions

of being rock stars

pretend to perform

their biggest hit

but in the wrong voice

in open protest

before a hyped-up audience

who only ask

for a pretext to dance

and clap in rhythm

for the cameras

as the singer misremembers

his no longer

subversive words

“load up on drugs

and kill your friends

it’s fun to lose

and to defend”

is now the message

behind the madness

that this methodical

falseness demands

he threatens to swallow

the microphone

the only one live

on the phony stage

in the phony BBC studio

in the crooning tone

of a different icon

to show them all

how low

the business of music

has sunk

how low

the once-spontaneous

communion

between poet

and expectant world