Gen X vs Millennials (Intergenerational Grievances Part 2)

It is the privilege of the young to blame their specific challenges on their elders, but who actually does worse depends on what you count, and how you count it.

In the spring in 1993, I graduated from McGill University in Montreal with a B.A. in philosophy, little in the way of marketable skills, and even less in the way of a sense of what I was going to do with my life. I had no job, and no real plan for how to get one. To some extent, that was just the result of my habitual inability to plan ahead. But the context mattered as well.

In 1993, Canada was a fiscal and economic basket case. The federal debt and deficit were out of control, and the country was just a few years away from being called “an honorary (sic) member of the third world” by the Wall Street Journal. The mild recession that had touched the U.S. had sunk its teeth deep into the Canadian economy: the national unemployment rate was over 12%, the national youth unemployment rate was over 17%. These figures were markedly higher in Montreal. Things were so bad that when the Montreal Canadiens won the Stanley Cup and fans celebrated by rioting and looting, the chaos was widely blamed on the economy.

To the extent to which Gen X is a Canadian creation (which is something I’ll argue in a future dispatch), these are the circumstances in which it was forged: we were, as Douglas Coupland had explained, the first generation to do worse than our parents, and the question of what to do with your life wasn’t an easy one to answer. Most people I knew just punted it for a few years. One friend went to ski and work at Whistler, another made a movie and paid for it with a hefty line of credit. A few others formed a band and gigged around town. I moved to Toronto and hid in graduate school.

Eventually the economy recovered, everyone got jobs and careers and families and the rest of it. The world unfolded as it does. Then along came the Millennials, born starting around 1981, who also started complaining about being the first generation to do worse than their parents. And as we saw in the last edition of this newsletter, this status is now being applied to Gen Zs as well.

So let’s settle this: Who really gets bragging rights as the most put upon generation since the Second World War?

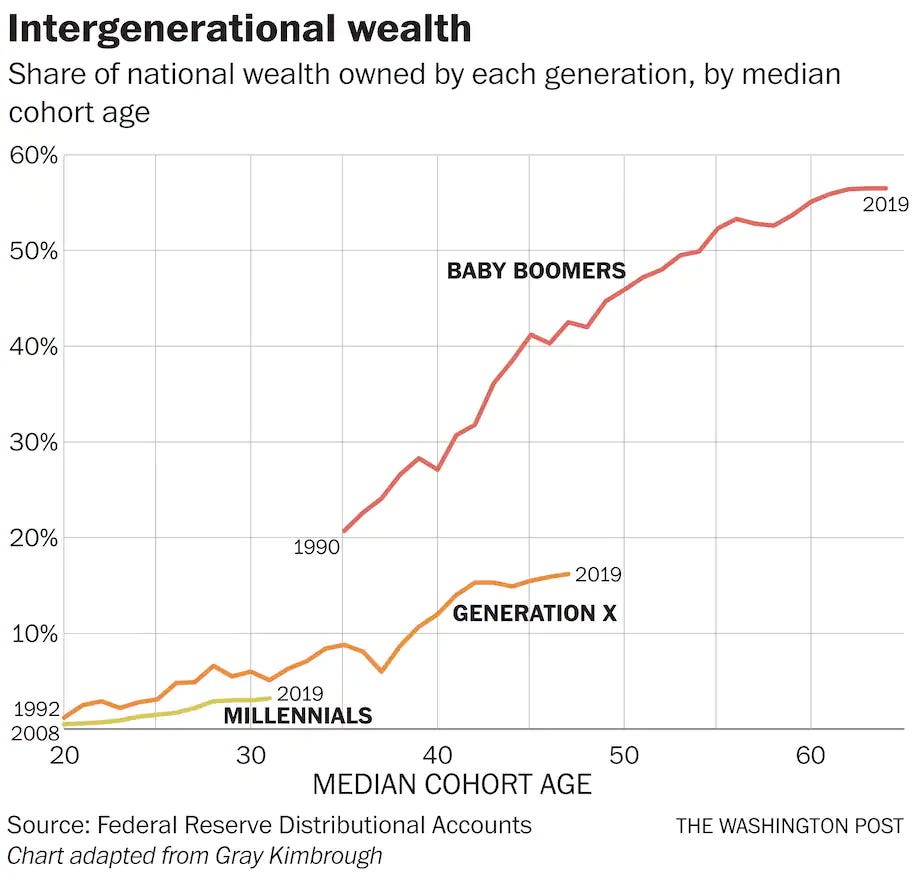

The answer, unsurprisingly, is it depends. It depends on how you count, what you count, and where you count, and how much weight you put on what you are counting. You can look at income, inequality, education, happiness, health care, home ownership, any number of measures that go into a life, and you can probably slice any of it however you like to get the answer you prefer. But to narrow our focus somewhat, let’s look at this one chart from the Washington Post:

When the Boomers were in their 30s, they controlled over 20% of the national wealth in the U.S., while Millennials at the same stage of life only have 3.5% of the wealth. First published in 2019, this has been widely circulated as the graphical equivalent of a mic drop. Case closed.

But maybe not! Don’t forget, there were a lot more Baby Boomers than Gen Xers or Millennials; when the economist Jeremy Horpedahl crunched the numbers and measured the share of generational wealth per capita, it turns out that Millennials are just as wealthy as the Boomers were at the same age, while Gen X is actually doing even better than their parents. Here’s the new graph:

This sort of data is largely consistent from one country to the next. In Australia, a strong majority of Millennials and Xers are earning more than their parents did; ditto for the United Kingdom.

Here in Canada, the situation is a bit mixed. In 2018, the Public Policy Forum published a report, written by Jennifer Robson and Andrée Loucks, on the financial situation of Millennials. They compared the finances of Gen Xers in 1999 to those of Millennials in 2016, and found that while the younger generation was more indebted, Millennials also had considerably higher income and assets than Gen Xers at the same stage of life. In his own write-up on the report, Alex Usher also noted that even the debt situation wasn’t as bad as it might appear, since repayment assistance for borrowers is a lot more more generous now than it was twenty years ago. Millennials also enjoy much lower interest rates (even with the recent increases) and tax burdens than Gen X did. Ultimately, Usher concludes that “there is almost no serious comparison one can make which suggest that Millennials are worse off than Gen X.”

The big elephant in the room here is housing. In almost every jurisdiction, the story is pretty much the same: if you look at per capita wealth, at similar stages of life Boomers and Millennials are pretty much at the same level, with Xers ahead. But if you index that wealth for the price of housing price, millennials are worse off. To put it simply, Millennials have lots of money, but no houses to spend it on.

There are optimists who think things will work out for the M generation. Jeremy Horpedahl thinks they’ll end up beating everyone in the wealth sweepstakes, while Alex Usher looks at the housing problem and sees an easy solution — just build more housing. That’s easier said than done, as Canadians are discovering, but it does raise the further question of whether we just put too much weight on home ownership.

As I said at the beginning, a lot depends on how you decide to slice the data, and how you weight the various elements. If there is any real takeaway here, it’s that each generation (except Boomers) has its burdens to bear. Gen Xers faced a wretched economy; Millennials are confronted by wretched housing market; The Zs are going to grow up in a world going to hell. It’s the privilege of each new cohort to hold their particular difficulties against their elders, as the definitive mark of how they’ve been screwed.

But to take it back to that spring of 1993, there is one thing that strikes me about that time, and it is this: the high unemployment, the debt, the apparent lack of opportunity — it didn’t really bug us all that much. There didn’t seem to be anything fundamentally broken about the economy, or the world. There were opportunities around, and if push came to shove, there was always law school, or business school, or if you were paying attention, this new thing called The Internet.

Sure, things were bleak. But I don’t know anyone who genuinely thought things would stay that way. We were kind of just bumming around not because we had no other options, but because we could. We were young, jobs and careers and families and houses could wait.

The media noticed, and as it tends to do, made a thing about it. They called us “Slackers”, and for a time, that was how Gen X was defined and — to some extent — how we defined ourselves.

That is the subject of our next dispatch.

The next few editions of Nevermind will continue with some basic brush-clearing. We’ll discuss the “Slacker” slur next, and then we will spend a bit of time looking at what I take to be the fundamental ideological commitment of Gen X, namely, the fear of selling out. — ap

If you like this newsletter, please share it around!

Many if not most Gen Xers were raised by thr Silent Generation or older boomers. Those are parents that had properties and investments tk pass on to us when they die. My friends parents are now dying or about to and we are inheriting properties and wealth of our parents. Boomers are now having to spend a huge portion of their wealth on elder care and eventually nursing homes and they are dipping into their wealth and selling the homes they bought for a dime in the 70s and 80s for a lot of money thay goes into that care that will not being going to their millenial kids.

A big advantage later generations have over GenX at the same age is the internet, particularly the edge it gives in job-hunting.

Also graduated in mid-90s recession, and NO ONE was hiring. I'd buy an Ottawa citizen and Ottawa Sun in the morning and check the classifieds for something to apply to. If there was one job that fit, I applied to one job that day. If none, than none. Other cities and regions? Forget about it. Apparently the job market in Calgary & the West was booming at that time, but if you didn't have family or someone you knew there then you had no clue it was booming. A city two hours away could be booming and you'd never know. With no internet, job leads came from your local paper and people you knew.

A real go-getting or desperate GenX'r back then would go to malls or the Market (restaurant&bar district in Ottawa) hoping to spot a Help Wanted sign, or even go into random businesses and ask if they were hiring. Tiring and futile for the most part, but I actually got part-time work that way one time.

Now a 20something can apply to as many jobs as they've got time to, and scoping the job market of other cities or even countries is a breeze.