Drunk and Reckless in the Age of Boredom

If there is one thing that enabled a lot of bad behaviour back in the eighties, it was the almost complete absence of widespread parental oversight

THERE WERE LOTS OF THINGS WE COULD GET AWAY WITH SAYING in our house; my parents weren’t too hung up on casual swearing, for example. But one phrase that was absolutely forbidden was “I’m bored”, and uttering it was liable to get you sent to clean your room, or worse.

But frequently bored, I was. When I try to conjure up the dominant mood of my high school years, what I remember almost the most is just how incessantly bored we were. There was lots to do of course, between schoolwork and family life and extracurriculars; there were movies and music and parties, sports and other hobbies, lots of us got part-time jobs, some had boyfriends or girlfriends. But time seemed infinite; there were endless gobs of it lying about, stretching into the evenings and weekends and summers, like a great psychological desert. And more often than was healthy, we dealt with it by Getting Up To No Good.

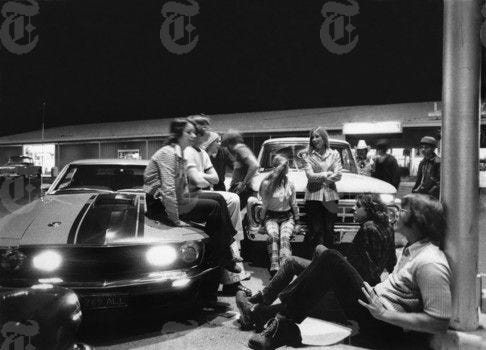

At the centre of it all, as enabler, partner, lubricant, participant, or distraction, was alcohol. We started drinking at a shockingly young age – some of my classmates were drinking by the end of grade nine, I started along with most of my friends in grade ten. But by grade eleven, pretty much everyone I knew drank, and drank heavily. A good weekend was one where you got loaded one night, a great weekend was when you did so both nights. We were too young to get into bars, but it was easy enough to get booze – either from older siblings, stealing from parents, or from a trip across the Ottawa River to Hull, where the depanneur owners weren’t too hung up on checking for ID. So on weekends by night, we would gather in parks or by the river or in houses where someone’s parents had made the terrible mistake of going away, and we would drink.

Along with the booze came the loss of inhibition and impairing of judgment that gave rise to all sorts of risk-taking: from physical stunts, reckless driving, and other forms of self-destructive behaviour through to acts of minor vandalism or public mischief (a lot of which still seems too recent to safely talk about.) There was some experimentation with sex, though I think a lot less than many of us would have liked. But all of this got poured into the crucible of what seemed like endless time, where boredom acted as foil and forge of our adolescent identities.

We were not alone in this, not by any stretch. The second half of the 20th century could without much exaggeration be interpreted as the Age of Boredom, a period generously coloured by a general sense of tedium, ennui, apathy – whatever you want to call it. An large and influential sociological theory, known as the “critique of mass society”, was largely motivated by a belief in the essential dullness of modern life, in particular in its suburban aspects.

But what is boredom, anyway? It’s not just the fact of having nothing in particular to do. It is the negatively charged experience of that state, and it contrasts with the more positive sense of mere idleness, what the founder of The Idler magazine, Tom Hodgkinson, echoing Walt Whitman, calls “the pleasurable, harmless and completely cost-free pleasures of simply doing nothing in particular.”

But the late twentieth century had trouble with idleness, because there was always an alternative to having nothing to do, namely, television. As William Deresiewicz writes in a fabulous 2009 essay “The End Of Solitude”, it is no coincidence that the Age of Television and the Age of Boredom went hand in hand: “Television, by obviating the need to learn to make use of one’s lack of occupation, precludes one from ever discovering how to enjoy it… You are terrified of being bored – so you turn on the television.”

The problem with television, though, in the age before streaming, or even widespread easy recording, was that TV was a pure commodity, designed for wasting time. There was no real expectation that people would really care deeply about what they were watching, it existed solely to distract or, at best, mildly entertain the viewer. Waching television was what you did when there was nothing else to do. To that extent, it was just boredom made manifest – less a solution to the problem than a symptom of it. Hence, amongst my friends, the standard response to the teenage wasteland was risk taking and rebellion.

It would certainly be a wild coincidence if the well-documented rise of helicopter parenting had no impact at all on the drop in adolescent rebelliousness.

As far as we were concerned, this was nothing more than the natural order of things, baked into the very structure of our civilization. It was certainly completely normal behaviour by the standards of our peers, and as reflected back to us through pop culture. Yet some of the most interesting (and in some ways perplexing) social phenomena of the last three decades have been the significant declines in risk-taking behaviours amongst adolescents in high income countries. Whether it is binge-drinking, smoking, cannabis use, delinquent behaviours, or precocious sexual activity, the whole package of risk-taking activity amongst youth has been dropping steadily in Canada and the U.S. since the mid-1990s. One major study looked at the trends across the Anglosphere and the EU since 1990, and found similar results. The kids aren’t really behaving badly these days, at least by the usual measures, and while it is difficult to tease out the various causal factors, the hypothesis everyone keeps returning to is that it is a consequence of the enormous decrease in unstructured face to face time with friends. For example, during the 1990s four fifths of American 10th graders reported going to parties at least once a month, by 2017 this had dropped to about 57%.

This large drop in casual hanging out falls in lockstep with the rise of internet use, and seems to accelerate with the introduction of smartphones. This has led to a lot of armchair theorizing about a straightforward substitution effect, where (the argument goes) kids are now too busy texting one another or spending time online to have time for things like drinking and drug use, unprotected sex, vandalism, and so on. It’s not so simple, though, and there are probably a lot of other factors at work, including changing norms around parenting. It would certainly be a wild coincidence if the well-documented rise of helicopter parenting had no impact at all on the drop in adolescent rebelliousness. Indeed, if there is one thing that enabled a lot of our behaviour back in the eighties, aside from the booze and boredom and the time, it was the almost complete absence of widespread parental oversight, which gave plenty of room for peer pressure and status competition to wreak their havoc.

But however the question gets resolved, one thing is true, which is that no one really gets bored anymore – the portable, networked, smartphone-enable social internet has seen to that. If boredom was the great social malaise of the second half of the twentieth century, loneliness is the despair of the first half of the twenty first. As Deresiewicz puts it, just as boredom is the negative experience of idleness, loneliness is the negative experience of solitude. And just as spending countless hours watching television trained an earlier generation to be bored, “a hundred text messages a day creates the aptitude for loneliness, the inability to be by yourself.” Where Generation X never learned how to be idle, today’s adolescents are incapable of solitude.

This has led to a great deal of hand-wringing about the effects of smartphone use on mental health, and it is given some credence by studies showing that, compared to Gen X and even Millennials, members of Gen Z are much more likely to report feeling stressed, anxious, and lonely. But cause and effect remains hard to establish, especially given the extent to which we are all just much more comfortable talking about mental health than we used to be.

Besides, for all of our collective bravado, the boasting about being the latchkey generation, it’s not obvious that Gen Xers are doing all that great. What’s eating Generation X? We’ll pick that up in the next dispatch.

As always, thanks for reading. I’d appreciate you sharing this with anyone who might find it enjoyable as well. — ap

This is the third newsletter I've read in the last couple of days speculating on the changes in how GenZ kids entertain themselves versus how GenX kids did. I've even started on a newsletter of my own.

We are starting to see the first generation in human history that grew up inside become parents themselves. At least the GenX parents had some tribal memory of what it is like to play outside and without supervision. The next generation of parents will have never had that experience. I fear for what is coming.

Mid-Boomer but also with now 20 something kids. (Yes, I did collect CPP and the Child Tax Benefit for about 6 months.)

We homeschooled our boys largely because school seemed to have moved away from teaching towards becoming a peer group petrie dish with a dollop of "the Current Thing". Also because with the internet kids could explore, quite deeply, what they were actually interested in.

Our boys like to party, to a degree, but the younger one needs his licence for work so no drinking and driving. (Graduated licence, one drink and you're out.) The younger has a decent trades job, his own ancient BMW - which he bought - a delightful girlfriend and bunch of hockey bros/Magic players for friends. The older runs a BMW diagnostics shop in our garage, fixes college kids' cars, enjoys beating his father hollow arguing everything from law to history. Boredom paid off.

I don't think "vandalism" has ever occurred to either of them, but we did cut down and they carried back to the house, a 14 foot Christmas tree, in the snow.

My own view is that a lot of the "behavior" which occurred in my youth, and apparently yours, was mainly about a lack of opportunity to behave better. Our objective raising our boys was to give them plenty of opportunity to do well. We'll see how that turns out but, so far, they seem to have taken the opportunities offered.